Lost in the forest

In this post, I want to address why Bayesian modeling approaches, especially those implemented in Stan, should be considered as a valid alternative to common machine learning techniques in sports analytics. Specifically, I’ll focus on a well-established criterion for model evaluation: leave-one-out cross-validation (LOO-CV) and its use to calculate the expected log predictive density (ELPD). This scoring rule measures how well a model predicts unseen data. If you’d like a deeper explanation of ELPD and its interpretation in the context of this example, I’ll include one in an appendix at the end.

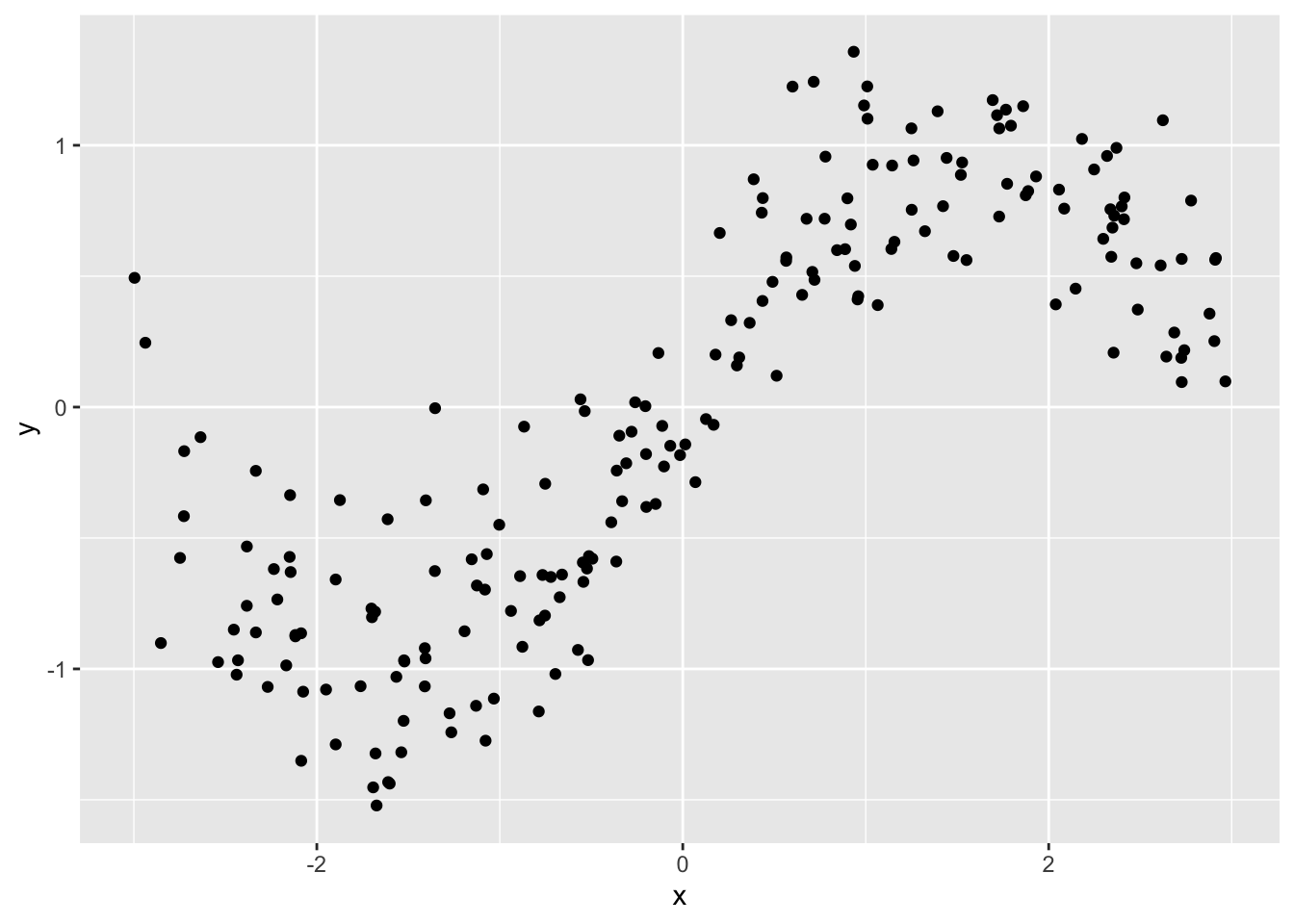

Let’s begin by generating some simple, non-linear data:

set.seed(123)

N <- 200

x <- runif(N, -3, 3)

y <- sin(x) + rnorm(N, sd = 0.3)

df <- data.frame(x = x, y = y)Here’s what our data looks like:

Modeling with Random Forests

Now, let’s try fitting a random forest model, a popular machine learning method. Random forests, while useful for finding patterns, don’t explicitly model uncertainty in predictions. Nevertheless, we can approximate the ELPD by predicting the mean and variance across trees:

library(randomForest)

predict_with_variance <- function(rf_model, newdata) {

all_tree_preds <- predict(rf_model, newdata = newdata, predict.all = TRUE)$individual

pred_mean <- rowMeans(all_tree_preds)

pred_var <- apply(all_tree_preds, 1, var)

return(list(mean = pred_mean, variance = pred_var))

}To calculate LOO-CV for the random forest model, we iteratively refit the model on training data with one observation left out at a time, predicting the left-out observation and accumulating the log-likelihood of the predictions:

loo_cv_random_forest <- function(data) {

n <- nrow(data)

log_lik <- numeric(n)

for (i in 1:n) {

train_data <- data[-i, ]

test_data <- data[i, , drop = FALSE]

rf_model <- randomForest(y ~ x, data = train_data)

pred_with_var <- predict_with_variance(rf_model, newdata = test_data)

log_lik[i] <- dnorm(test_data$y, mean = pred_with_var$mean, sd = sqrt(pred_with_var$variance), log = TRUE)

}

return(sum(log_lik))

}Here’s the result for the random forest’s approximate LOO-CV ELPD:

approx_elpd_loo <- loo_cv_random_forest(df)

approx_elpd_loo## [1] -393.1147Bayesian Gaussian Process in Stan

Next, let’s use a Bayesian approach. Specifically, we’ll fit the same data with a Gaussian process model using Stan, a flexible and probabilistic programming language that allows us to properly account for uncertainty. Nothing fancy, we’ll just grab the basic model described in the Stan User Guide:

data {

int<lower=1> N;

array[N] real x;

vector[N] y;

}

transformed data {

real delta = 1e-9;

}

parameters {

real<lower=0> rho;

real<lower=0> alpha;

real<lower=0> sigma;

vector[N] eta;

}

model {

vector[N] f;

{

matrix[N, N] L_K;

matrix[N, N] K = gp_exp_quad_cov(x, alpha, rho);

// diagonal elements

for (n in 1:N) {

K[n, n] = K[n, n] + delta;

}

L_K = cholesky_decompose(K);

f = L_K * eta;

}

rho ~ inv_gamma(5, 5);

alpha ~ std_normal();

sigma ~ std_normal();

eta ~ std_normal();

y ~ normal(f, sigma);

}

generated quantities {

vector[N] f;

{

matrix[N, N] L_K;

matrix[N, N] K = gp_exp_quad_cov(x, alpha, rho);

// diagonal elements

for (n in 1:N) {

K[n, n] = K[n, n] + delta;

}

L_K = cholesky_decompose(K);

f = L_K * eta;

}

vector[N] log_lik;

for (n in 1:N) {

log_lik[n] = normal_lpdf(y[n] | f[n], sigma);

}

array[N] real y_pred = normal_rng(f, sigma);

}After fitting the model with Stan, we calculate the LOO-CV ELPD, where uncertainty is fully propagated through the model:

library(cmdstanr)

dat <- list(N = N, x = x, y = y)

m <- cmdstan_model('basic_gp.stan')

f <- m$sample(data = dat, adapt_delta = 0.99, refresh = 0)f$loo(cores = 4)

Computed from 4000 by 200 log-likelihood matrix.

Estimate SE

elpd_loo -41.0 10.0

p_loo 8.2 1.4

looic 82.1 20.0

------

MCSE of elpd_loo is 0.1.

MCSE and ESS estimates assume MCMC draws (r_eff in [0.8, 1.7]).

All Pareto k estimates are good (k < 0.7).

See help('pareto-k-diagnostic') for details.The Result: Why Bayesian Methods Win

When comparing the LOO-CV ELPD from the random forest to that of the Bayesian Gaussian process, the difference is stark. The ELPD tells us how well the model generalizes to unseen data. The Bayesian model produces a much higher ELPD, meaning it makes better probabilistic predictions.

Now, let’s discuss why this happens. A key concept in understanding this is Jensen’s inequality, which states that:

\[ \mathbb{E}[f(X)] \neq f(\mathbb{E}[X]) \] for a convex or concave function \(f\). In other words, the expected value of a function of a random variable is not necessarily the function of the expected value of the random variable. This becomes important in machine learning models, where people often use point estimates as inputs to non-linear models like random forests.

When random forests predict an outcome, they use the mean prediction from many trees. However, due to Jensen’s inequality, using the mean prediction can lead to biased estimates in the presence of non-linearity, because the variance in the model is not properly accounted for. Bayesian methods avoid this issue by directly modeling the full probability distribution rather than a point estimate.

By using a Bayesian approach, not only do we achieve better predictive performance as shown by ELPD, but we also gain the advantage of interpreting results in a probabilistic framework. This can provide deeper insights into the data, offer reliable uncertainty quantification, and ultimately lead to more informed decision-making in sports analytics.

Let’s not get lost in the forest. If you’re interested in learning more about Bayesian methods and Stan, feel free to join me in my online Bayesian data analysis course using Stan: https://athlyticz.com/stan-i

Appendix: a deeper look at LOO-CV ELPD

As mentioned, Expected Log Predictive Density (ELPD) is a scoring rule used to evaluate the predictive performance of statistical models, especially in Bayesian settings. It combines elements of how well a model fits the data and how well it generalizes to unseen data, making it especially useful for model comparison.

The ELPD essentially evaluates the average log probability of the observed data points under the model’s predictive distribution. More formally:

\[ \text{ELPD} = \sum_{i=1}^N \log(y_i \mid \text{model} ) \]

where:

\(y_i\) is the observed data point,

\(p(y_i \mid \text{model})\) is the predicted probability of observing \(y_i\), based on the model’s posterior predictive distribution.

The log probability measures the likelihood of observing the actual data point \(y_i\) given the model’s predictions. Higher values indicate better predictions (i.e., the model assigns high probability to the observed data). That it’s expected reflects the average predictive distribution for unseen data, taking into account the uncertainty in the model parameters. ELPD is typically reported in log units. Since it sums log-probabilities across data points, the total ELPD can be thought of as the average log-probability that the model assigns to each observation.

A higher (less negative) ELPD indicates a better predictive model. It show that the model is assigning relatively higher probabilities to observed data points. The scale of ELPD is influenced by the number of observations \(N\). This means that in practice, ELPD tends to be lower (i.e., more negative) for larger datasets. It can be normalized by dividing by \(N\) to give an average log predictive density per observation.

In practice, especially when evaluating model generalization, we often compute ELPD using leave-one-out cross validation (LOO-CV). The process looks like this: for each data point \(y_i\), fit the model using all other data points except \(y_i\). Predict \(y_i\) using this model, and calculate its log predictive density. Sum the log densities over all data points.

LOO-CV provides a more honest estimate of ELPD by mimicking out-of-sample prediction. ELPD is commonly used to compare models. Given two models, the one with a higher ELPD is considered to have better out-of-sample predictive performance. When comparing models, the difference in their ELPD scores helps us assess which model generalizes better to new data.

Example comparing the random forest and the Stan model

Let’s consider the two LOO-CV ELPD scores from the random forest model and the Bayesian Gaussian process, both pretty much right out of the box, so to speak:

For \(N=200\) observations, if the ELPD values are −393 for the random forest and −41 for the Stan model, here’s how to compute the average log predictive density per observation:

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{Average log predictive density (random forest)} &= \frac{-393}{200} = -1.965 \\ \text{Average log predictive density (Stan)} &= \frac{-41}{200} = -0.205 \\ \end{aligned} \]

Interpretation of the Average Log Predictive Density

The average log predictive density reflects how well the model predicts individual data points, on average. Larger values (closer to 0) are better, meaning the model assigns higher probabilities to the observed outcomes. With an average log predictive density of −1.965, the random forest model is assigning lower probabilities (closer to zero) to each observed data point, suggesting that its predictions are relatively poor. With an average log predictive density of −0.205, the Bayesian model is assigning much higher probabilities to each data point, meaning its predictions are much more accurate. You can convert the average log predictive density into an average probability (although this is less common) by exponentiating the value:

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{Average probability (random forest)} &= \exp(-1.965) \approx 0.14 \\ \text{Average probability (Stan)} &= \exp(-0.205) \approx 0.82 \\ \end{aligned} \] The average probability tells you, roughly, how confident the model is in predicting the actual observed values. A higher average probability means the model is much better at capturing the true underlying data-generating process. In this case, the Stan model is far superior to the random forest. This kind of analysis reinforces why ELPD is such a valuable metric for comparing models—particularly in terms of generalization and predictive performance.